PIs: Santiago Jaramillo of Biology and Melissa Baese-Berk of Linguistics

Being fluent in a second language is becoming more valuable as our society continues to globalize. Linguists have long studied the different ways that individuals acquire language, but if we could identify the neural mechanisms that contribute to second-language learning, perhaps we could more easily study a second language. Santiago Jaramillo in the Department of Biology and Melissa Baese-Berk of Linguistics aim to do uncover these neural mechanisms.

Through a National Science Foundation $1 million grant, Jaramillo and Baese-Berk plan to develop better strategies for second-language learning through combining experiments in both humans and mice. Current neuroscience tools for research in humans lack the necessary precision to uncover what neural mechanisms underlie language acquisition behaviors, but they hope animal models can provide such precision.

The impetus for this project comes from a phenomenon Baese-Berk has observed, in which periods of active learning sessions of a language can be replaced with passive exposure, and the result is equivalent to active learning alone. Even though mice don’t speak, they can learn to differentiate a wide variety of sounds, including those from human speech. If that process is similar to how people familiarize themselves with speech sounds, we may be able to use a detailed understanding of that process in mice to make the language learning process easier for people.

Baese-Berk will be looking at which exact mixes of active and passive learning are effective, and Jaramillo’s lab will focus on the neural processes using tasks where mice demonstrate recognizing speech sounds.

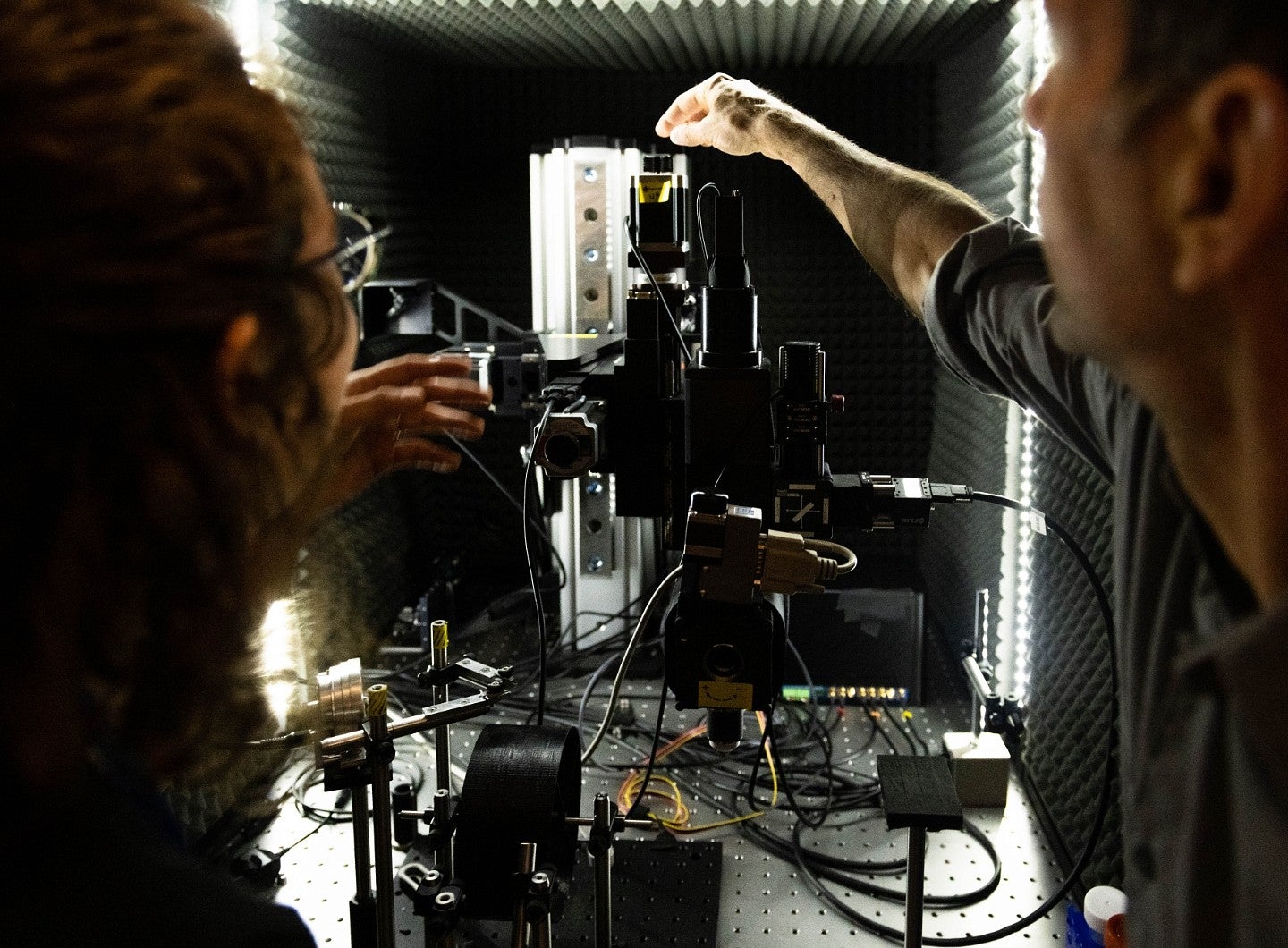

“This gives us the opportunity to directly relate the neuroscience work we do in the mouse to human behavior, which is something that’s not always straightforward when working with animal models,” Jaramillo said. “We will be using novel experimental and computational techniques, and developing new techniques is one of the most enjoyable parts of doing research. Their application will inspire other ways to use them to address important questions related to the neuroscience of cognition.”

Jaramillo also points out that in the long term, this research program has the potential to improve human communication, particularly when it comes to connecting people across different cultural and language backgrounds. If someone studying another language can know the right balance between active learning and passive exposure to the sounds of a new language, then they can learn more efficiently.