Who's Afraid of a Big, Bad Planet?

The planet is an active place. It rumbles, it blasts with magma, its sea levels rise. For the billions of people on Earth, these ordinary movements can have deadly consequences.

College of Arts and Sciences researchers are studying the forces that have made the Earth what it is today but also what makes it a hazardous place.

Work by CAS researchers John Christian, Leif Karlstrom and Brittany Erickson can help us understand the geologic past so we can have more insight into future changes to the planet. Whether studying earthquake data, ice sheet loss in Greenland, or past mega volcanic events, these researchers are working to change how we perceive hazards.

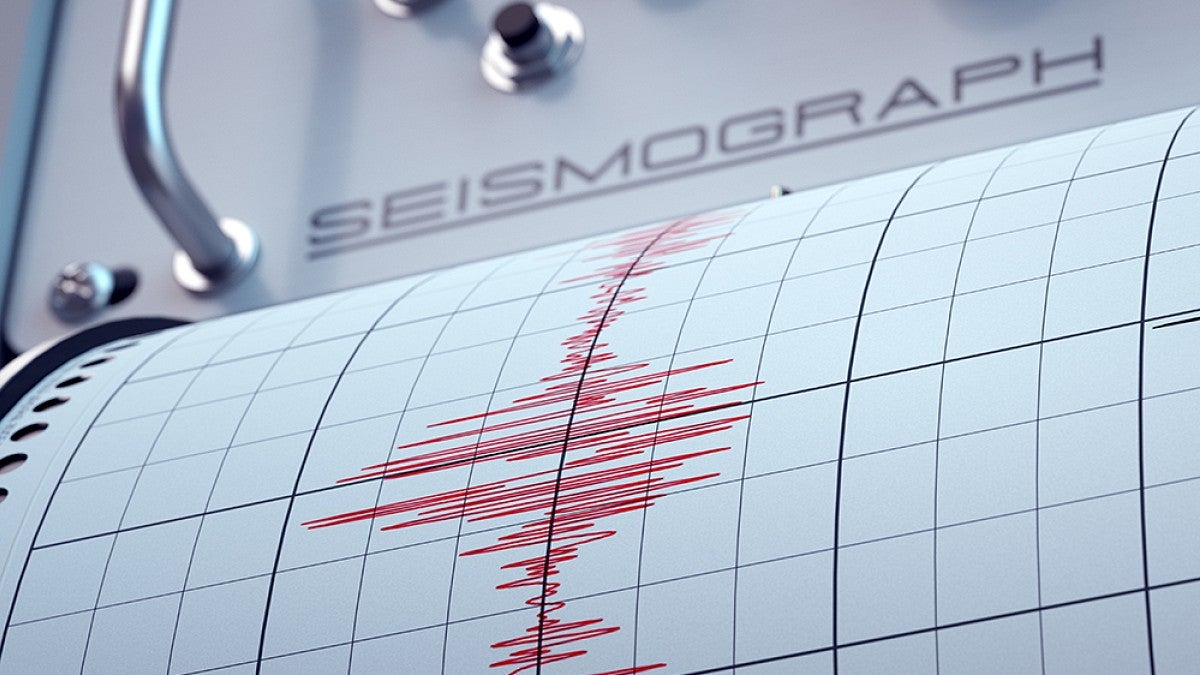

Gathering data from earthquakes

The Earth’s crust is moving. The planet’s tectonic plates are shifting, crashing and some are moving beneath each other. This movement can lead to devastating earthquakes for people around the world, but it has played a part in creating the planet’s rich geological landscape. Unfortunately, these ground-shaking events pose hazards for people living near seismically-active areas, including damage to infrastructure, tsunamis, landslides—and more.

Brittany Erickson, a computer science and Earth sciences associate professor, is leading research funded by a five-year, $720,440 National Science Foundation CAREER grant that explores the use of artificial intelligence for better understanding earthquake processes and how it performs compared to current methods.

“There are some clear areas where AI is doing important things,” Erickson says. “But it's not a panacea. It's not going to solve all our problems. Anytime it's used in an application area, you really need to ask yourself if what you're doing is offering any benefits to your community or the environment, etc.”

Earthquake faults below ground are almost impossible to measure firsthand. Scientists rely on instrumentation at the Earth’s surface, along with mathematical models to represent earthquake faults and seismic activity, but it’s a challenging computational task.

Using a Physics-Informed Neural Network, Erickson and her research team are exploring whether AI can speed up earthquake models used to predict processes occurring at depth. To test the program, Erickson will see how it performs with already-known faults and seismic activity data. From there, she and her team will apply the AI program to seismic data from faults at Cascadia (in the Pacific Northwest) and the Nicoya Peninsula of Costa Rica, which is prone to earthquakes.

Over the years, Earth scientists have collected a massive amount of earthquake data, and AI has the potential to excel when it has high-quality data, Erickson says. One goal for this project is to gain insight on what’s happening miles below the planet’s surface, which can be a part of earthquake forecast modeling.

The research is about more than just understanding earthquake data for the sake of hazard forecasting. Erickson says she’s using an applied mathematics approach to investigate big datasets and artificial intelligence, with the goal of being a good steward of AI. Research like Erickson’s is a way to see how well AI models are performing.

“Are they actually helping us solve the mathematical equations either better or faster, or are they enabling larger simulations to be solved at all?” Erickson asks. “Part of the plan in my research is to basically explore how well these methods compare to our traditional schemes, because if they're not going to do better, then we should not be using them.”

Brittany Erickson

Computer Science and Earth Sciences: AI and

earthquake monitoring

Received $720,440 from the National Science Foundation to explore whether artificial intelligence can help scientists predict seismic activity.

Keeping watch on Greenland’s ice melt

The ice sheet in Greenland forms the second largest body of ice in the world, but it’s melting into the ocean at an accelerated rate due to increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Ice sheets don’t melt overnight. Greenland’s changes in ice flow are a long-term reaction to increased air and water temperatures, according to John Christian, a glaciologist and assistant professor in the Department of Geography.

Through a three-year $361,775 National Science Foundation grant that ends in 2026, Christian is studying an early period of Greenland’s ice melt, which will help scientists today have a better understanding of the observed ice loss in the climate context of the last century and to project what the future could look like as the ice melt and sea levels rise.

Most research has examined the accelerated ice melt there in recent decades, but about 100 years ago, the region saw high levels of melting and retreating. “In the 1920s and ’30s, there was a period of pretty rapid warming in Greenland, and we know that some of these big glaciers that drain the ice sheets started retreating then,” Christian says.

Like an ice cube in a warm glass of water in a heated room, glaciers over time have been melting as the Earth’s air and oceans get warmer due to climate change. Because of modern monitoring technologies, like satellite observation, Greenland’s recent glacier loss has been studied intensely. But what happened 100 years ago in Greenland has been more difficult to study because of the dearth of monitoring capabilities.

One of Christian’s broader research interests is the timeline of glacial melting. Increased ice melt is an immediate reaction to warming. That then changes into ice flow on a slower timescale, Christian says. Because glacier flow takes a long time to respond to a changing climate, this means that with the melting that occurred in the 1920s, there should have been continued changes in flow in the following decades when more technologically advanced monitoring was established.

“The goal of this project is to try to understand the kind of implications of that earlier warming period,” he says. “We’re trying to get a fuller picture of the beginnings of the response of the Greenland ice sheet to industrial era climate change.”

Christian and his research team will create computer model simulations to run experiments to understand how ice sheets react to climate changes during different time scales. The model analysis that Christian will apply in his research will be led by postdoctoral researcher Schmitty Thompson, who brings expertise from previous research on ice sheets and sea level in Earth’s past climates.

“These ice sheet models are a big ingredient in making sea level rise projections,” Christian says. “To predict how much more the Greenland ice sheet is going to contribute to sea level rise in the next century, there’ve been these huge efforts to get all these modeling groups to run simulations and make projections about the future.”

Because ice sheets have a long response time to climate changes and reflect past fluctuations, projections face limitations by not including previous ice sheet losses. By focusing on the ice sheet loss of the 1920s and ’30s, Christian’s work could inform future Greenland ice sheet losses.

As glaciers and ice sheets continue to warm and discharge into the ocean, the planet will see an increase in sea levels. According to NASA, if all of Greenland’s ice were to melt into the ocean, the sea could rise by about 23 feet, which would pose a threat to many of the world’s coastal cities.

The uncertainty of how much ice sheet melting will contribute to sea level rise, though, remains one of the largest unknowns of climate change—besides the rate of how much greenhouse gas emissions humans continue to emit.

Over the last 100 years, a sea level rise of nearly 20cm (or eight inches) has increased coastal impacts. Understanding what drives sea level rise can help scientists see the impacts in context, Christian says.

“Coastal communities and planners need these projections,” Christian says. “They need the best estimates and estimates of uncertainty. We also gain context from understanding past changes better.”

John Christian

Geography: Greenland ice melt

Received $361,775 from the National Science Foundation to study an early period of Greenland's ice melt for insights that could help scientists predict what a future of rising sea levels could look like.

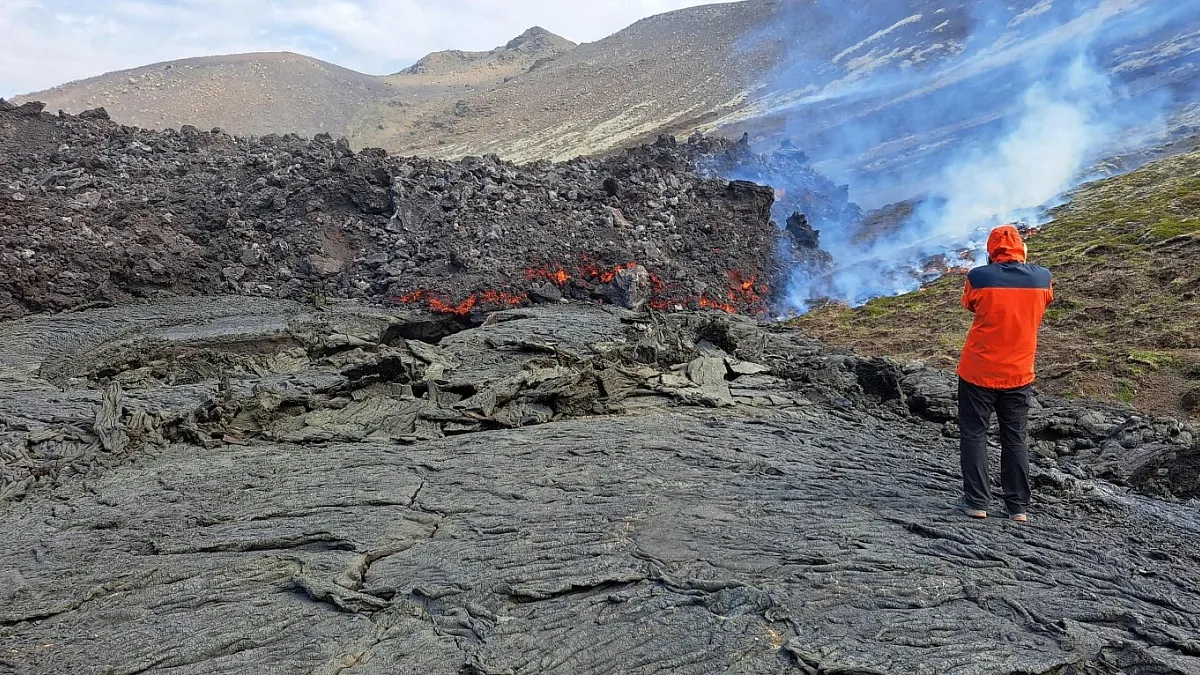

Studying ‘the biggest, baddest’ volcanoes

Throughout the Earth’s 541 million years, the planet has gone through five mass extinctions of species, four of which have been influenced by what are called large igneous provinces. Large igneous provinces are on the extreme end of volcanoes, events that erupted lava and magma onto the Earth’s surface.

Large igneous provinces are key to understanding how modern volcanoes function, says Leif Karlstrom, an Earth sciences professor. With a four-year $773,132 National Science Foundation grant, Karlstrom is the co-lead principal investigator of a research team studying large igneous provinces and how the Earth has reacted to these mega volcanic events. The research endeavor is led by Rutgers University with collaborators at University of California, Davis; Virginia Tech; Oxford University; and Leeds University.

“If we want to understand how volcanoes work in any setting, including the modern and the ones we care about for geo hazards and mitigating those hazards, we’d better understand the biggest, baddest ones out there,” Karlstrom says. “And that’s large igneous provinces by a long shot.”

The Earth hasn’t seen a large igneous province erupt in a long time, but Karlstrom says there’s a lot that can be studied. The massive amount of magma and lava flows that these events produced historically—many millions of years ago—altered the Earth’s climate, creating major climate disruptions. In a geologically short time, these events emit significant levels of heat and gases, such as carbon dioxide and sulfur. But what is less known is how the planet reacts, Karlstrom says.

“Because the mantle is melting, you have large volumes of magma being produced,” he says. “That magma doesn’t have to get to the surface. The carbon dioxide can decouple from the magma and rise through the crust and still influence the climate without ever seeing any magma at the surface.”

In an October 2024 issue of Nature Geoscience, Karlstrom was part of a research team that published a study revealing that a large igneous province in Siberia continued to emit carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Known as the Siberian Traps, the volcanic activity continued to expel carbon dioxide for millions of years after eruptions.

Karlstrom and the team of researchers will spend time looking at examples of large igneous provinces in Wallowa County in eastern Oregon and the North Atlantic Igneous Province, which spans the United Kingdom, Iceland and Greenland.

The Pacific Northwest is home to one the youngest products of a large igneous province. Formed by more than 350 lava flows from 16.7 million years to 5.5 million years ago, the Columbia River Basalt Group—located in eastern Oregon and stretching out to western Idaho and eastern Washington—is an example of flood basalt activity that has erupted more than 350 lava flows, according to the US Geological Survey.

For this research, Karlstrom is developing a mathematical framework that can use the data to guide predictions. The team is developing models of cycles of previous large igneous province eruptions to understand the processes that led to the decoupling of gases that percolated through the planet’s crust. “Why did the eruptions shut off and gas get out? What led to that?” Karlstrom says. “We’re interested in understanding the full range of magma processes from mantle to the atmosphere.”

And large igneous provinces not only help scientists like Karlstrom understand volcanoes and the hazards they pose, but they also have broader applications for studying how the planet reacts to climate changes, including the one we’re in today.

“If you want to understand the current perturbation to the planet, the best place to look at is the geological record,” Karlstrom says. “We can use these past perturbations to understand what’s the likely trajectory out of our current state.”

Leif Karlstrom

Earth Sciences: Mega volcanic events

Received $773,132 from the National Science Foundation to study how our planet reacted to the massive volcanic events that helped shape its surface.

—By Henry Houston, College of Arts and Sciences

Inspiring Future Scientists

As part of these National Science Foundation awards, John Christian, Brittany Erickson and Leif Karlstrom are using some of the funds to support students and recent graduates, as well as people in underrepresented communities of the Pacific Northwest.

While Christian and postdoctoral researcher Schmitty Thompson research the rate of ice sheet melting in the 1920s-30s, Christian will work with undergraduate students. The undergrads will develop additional computational projections of ice sheet flow, including how it fluctuates (Henry Axon, physics) and how it’s influenced by surrounding topography (Isabelle Below, computer science).

Funding undergraduate projects was part of the goal of the grant, Christian says. “It wasn’t just to fund a student to turn the crank on something but to fund a full-time summer gig that could be their own project,” he says.

Brittany Erickson is working to inspire future data, Earth and computer scientists. Through the NSF grant, Erickson will provide two-week paid internships to Lane Community College students in Eugene to improve their analytic and computational skills. Erickson will mentor them as they improve their computer coding skills, develop an understanding of the mathematical equations used in earthquake modeling and learn how to integrate observational data into deep learning algorithms.

“They’ll also learn other necessary skills for doing team research,” Erickson says. “Ambitious, I know.”

As Karlstrom studies a large igneous province in eastern Oregon, he’s going to organize events in Wallowa County to connect rural communities with scientists around the world, he says. “We’re doing some outreach in northeast Oregon, visiting schools, providing the opportunity to interact with scientists,” he says.