Experiential Learning | Research & Innovation | Community Impact | Career Preparation | Teaching Excellence | 21st Century Liberal Arts | Building Community | Good Vibes | CAS Spotlights | All Stories | Past Issues

How Criminal Trials Become Cultural Debates

JANUARY 2, 2024

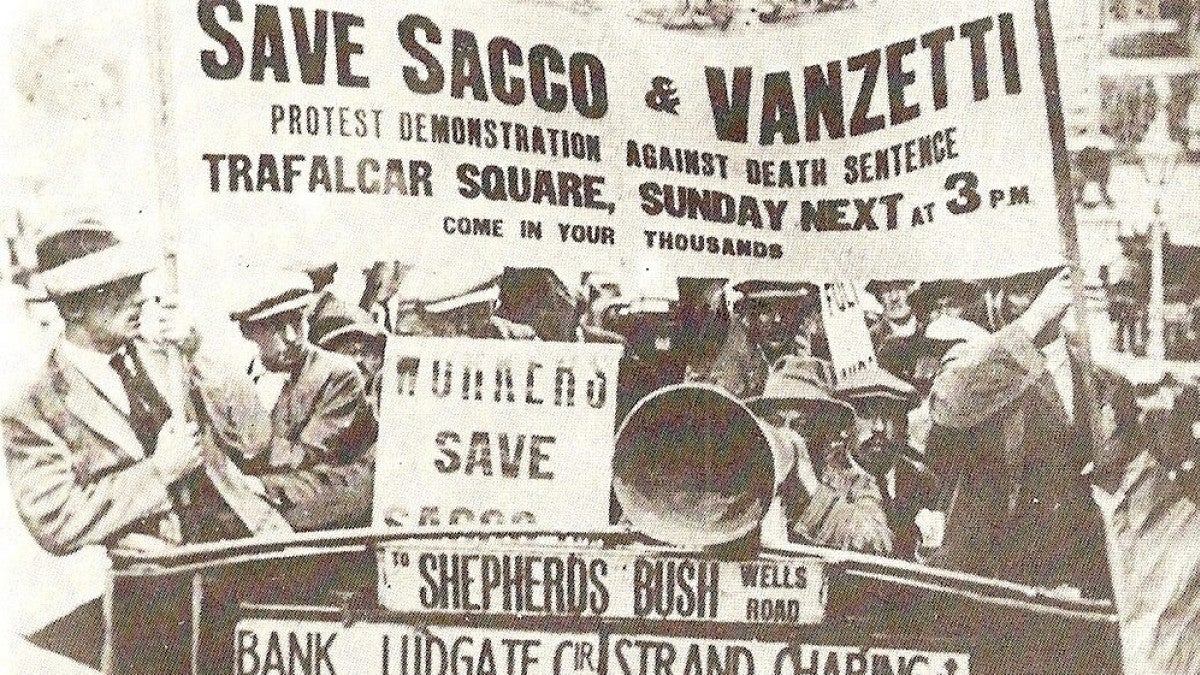

When Italian immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were convicted of robbery and murder in 1921, their trial became a media sensation, exposing prejudice and injustice in the US judicial system.

Despite protests and public outcry over evidence they had received an unfair trial, the men were executed. But their case lives on in the minds of such scholars as Mark Whalan, a professor and head of the English Department in the College of Arts and Sciences, who sees a strong parallel in the media’s role in turning criminal trials into public cultural debates both then and now.

Throughout his academic career, Whalan has studied how literature reflects and impacts societies, politics and public opinion. With an MA in English Literary Studies and a PhD in American Cultural Studies, he examines the use of literature in the United States as a tool to “create and motivate publics.”

His latest academic article, “The Public and its Problems: Sacco and Vanzetti, Dewey, Dos Passos, and Activist Literary Publics in the 1920s,” discusses the cultural power literature had in the post-WWI political era. The paper will publish in the Spring 2025 issue of English Literary History academic journal.

In his essay, Whalan compares the media landscapes of the 1920s and the present day, remarking on parallels between the two. Though the technologies and policies that affect the spread of information differ, the political impacts of a rapidly changing media and entertainment landscape in the '20s have clear resonances with our own era.

While the parallels aren’t precise, they are important considerations for scholars like Whalan.

“There's always a danger in historians trying to draw parallels that are too exact between events in history and things happening now,” Whalan says. “But at the same time, I think exploring how certain dynamics of our political and cultural experience seem to be enduring features of our national history is useful work for scholars to do.”

Whalan’s interest in the trials of that period stemmed from his research for his book World War One, American Literature, and the Federal State, in which he examined how authors sought to represent and sometimes to intervene in the political concerns of the day on topics such as the size and function of the federal state; immigration; and health care.

—Mark Whalan, professor and head of the English Department

Whalan notes one significant difference in public opinion between then and now: the technology available to spread information. In the early 1920s, TVs didn’t exist, movies didn’t have sound, and radio was still in its early years.

Although print newspapers were the central medium for distributing news and political information, Whalan says, people also looked to poetry and novels for guidance. Poems like Edna St. Vincent Millay’s “Justice Denied in Massachusetts” appeared in prominent newspapers like the New York Times, while novels like John Dos Passo’s U.S.A. trilogy explored the Sacco and Vanzetti case in the years following the trial. This rapid production of media surrounding notable trials still occurs now, though often in the form of audiovisual media such as streaming docuseries or true crime podcasts.

“It's hard to relate to now, but in the 1920s major newspapers would place poems dealing with issues of the day in very prominent locations,” Whalan says. “Some widely read novelists and poets took it as their central mission to sway their readers to a certain politics, or to shape their views on specific issues of the day. Some very popular authors based their whole careers on this premise.”

While not impactful on a daily basis, novels had the advantage of being able to capture the entirety of an event, rather than a snippet of it.

“Novels are a lot less nimble than newspapers or poetry,” he says. “They take longer to write, take longer to read, are way more expensive to publish, distribute and buy, and would usually have a smaller readership when compared to an occasional poem appearing in a prominent newspaper. All that made them less capable of reacting in the moment to news. But they are better, perhaps, at capturing the entirety of a political and cultural climate at a moment of crisis.”

Whalan hopes his essay reveals how closely related the Sacco and Vanzetti case was to the way the American public got their information in the 1920s. It’s also important to understand that literary authors were considering these issues similarly to the political philosophers of the day, who were concerned that new media and entertainment were eroding the effective functioning of American democracy, he adds.

The Sacco and Vanzetti case offers insight into how an earlier era faced challenges such as a crisis of low and/or misleading information; how distractions—often a modern entertainment industry and innovative new media—had drained attention away from issues of urgent political concern; how the country was problematically fractured on any number of contentious political issues; and how government institutions were poorly equipped for these challenges.

As Whalan says, it provides “a fascinating and salutary example of how a previous generation of Americans dealt with issues that seem so pressing and preoccupying today.”

—By Grace Connolly, College of Arts and Sciences