August 5, 2024 - 9:00am

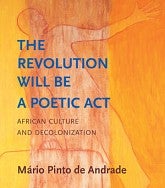

Mário Pinto de Andrade was a prolific anticolonial writer, poet and politician but because his writing was mostly in French, Portuguese and Spanish, his work has been relatively inaccessible to those who can't read those languages. Lanie Millar and Fabienne Moore, both associate professors in the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Romance Languages, collaborated on a project to make his work more accessible with “The Revolution Will Be a Poetic Act: African Culture and Decolonization.” The book has 14 of Andrade’s essays and speeches translated from French and Portuguese into English and was published by Polity in August 2024.

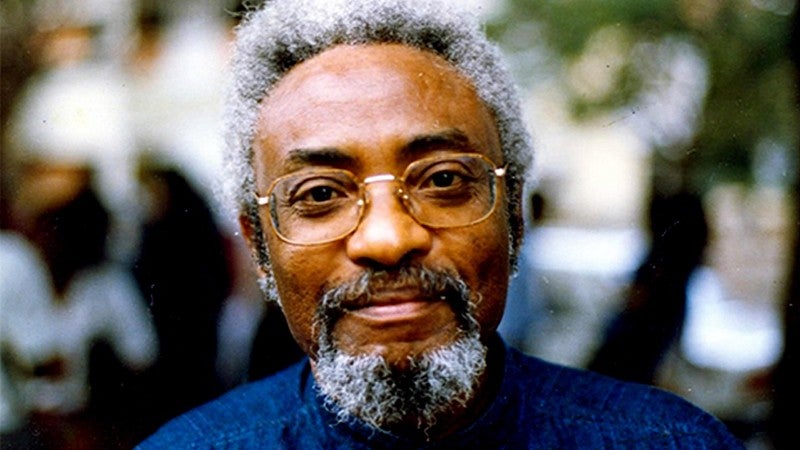

Born in the African country of Angola during Portugal colonial rule, Mário Pinto de Andrade is one of the most important Portuguese-speaking intellectuals in Africa. He is one of the founders of the party that came to power in Angola after its independence but was then exiled by the party's leaders. He never returned to or became a citizen of independent Angola, living outside the country for his entire adult life.

Along with the translated essays and speeches, the book includes a foreword from Millar and an interview with Andrade’s two daughters, Henda Ducados and Annouchka de Andrade, who are guardians of his work. Millar is also helping them find an organization to properly archive and house Andrade’s collection. Millar, who teaches Spanish and Portuguese, and Moore, who teaches French, both took time out of their busy publishing and teaching schedules to talk about the origin of their interest in Andrade, how they came together for this project and its impact.

Who is Mário Pinto de Andrade to you?

Lanie Millar: One of my research specialties is Portuguese-speaking Africa, and particularly the period leading up to independence. I was fascinated by his work in general and by the place he held in the history and context of Portuguese-speaking African decolonization. He's one of the most important chroniclers of that period of mid-20th to late-20th century cultural development in that area, writing from the perspective of multiple different audiences in different languages, translating and explaining the independence fights. And yet, because he wrote in French and Portuguese, and he was outside of Angola, he has never been fully embraced by the national state establishment in Angola. Everyone knows about him, but they don't really read him carefully.

Fabienne Moore: Andrade was a multilingual, multicultural Black intellectual from the 20th century. He is a lesser-known voice who is incredibly persuasive and eloquent about questions of revolution. I care to understand how people live through revolutions, how they foment revolutions, what are the consequences of the revolutions, and he is one of those figures. He had a very moving life.

How did this become a project for you?

LM: It started off as a standard professor research project. I was interested in some of the introductions to poetry anthologies that he wrote and looking at the way that he was thinking about Black identity in the face of anti-Black colonial politics and then tracing what writers and poets had contributed to it. In the course of that research, I realized there's so much material that is not easily available. My initial thought was that I was going to translate five of his introductions to anthologies. Then as I kept digging, I realized there was much, much more material, and a significant amount of material in French. I thought the picture of his intellectual production would be incomplete if I just focused on Portuguese, and I approached Fabienne to collaborate.

FM: I have this spirit of curiosity. I'm always curious about the next thing, and I love to get involved with something new. When Lanie approached me about the French translations, I was inspired by a spirit of curiosity and a little bit of, "How come I don't know about this?" I wanted to know more and also practice collaborating because scholarship today in the humanities benefits from being collaborative.

What are some challenges with translating his work in these languages to English?

LM: Andrade had an incredible flexibility with toggling among registers. He wrote with phrases and words that meant a particular thing in the context of the circles that he was talking to at the time. We had to work on the best way to capture his wordplay and his figurative language. The challenges in translating were in both the particularity of his voice and his context and who he was speaking to. And then also the size of the project and making sure that what we settled on sounded in English like the way that we thought he sounded in French and Portuguese.

FM: The challenge is what happens when you travel between languages, which is what translation is about. You really get a sense of the genius of each language and the spirit of each language. And what is remarkable about Andrade is that he had a complete mastery of the French, the Portuguese and the Spanish languages. The challenge is how then to travel between this very elaborate, absolutely high register French into idiomatic English, where it reads fluently without a clunkiness that one would add if we were to respect the French original’s twists and turns. We had to strike a balance between being faithful to the initial French and at the same time wanting an English version that is accessible and fluid.

What are some discoveries you've made in reading these essays?

LM: I started off the project thinking of him as the theorist of this poetic movement in the 1950s, primarily in Portuguese, and discovered over the course of the work the incredible range and insightful contributions that he made to thinking about what should revolution look like, what should societies look like after they've gone through a process of armed struggle and revolutionary decolonization? He was really prescient about thinking about the problems that would come after independence. I wouldn’t have discovered the richness of his work if we hadn't been working with these texts so closely. The process of translation brought those out for me.

FM: For me, I discovered how a very deep thinker could have an impact on politics and academia. For the longest time, and it's still the case in some countries, the idea was that thinkers are there to help think through political issues. And this is exactly what Andrade did. He would write a manifesto to put ideas out there about independence and liberation.

How does the University of Oregon make this work possible?

LM: Something that is unique about the UO, and that is absolutely a reason that this project came to be as it did, is that we are in a romance languages department where our department teaches four different languages. We are in close contact with each other, and we collaborate. A figure like Andrade, who traveled all over the world, who lived in many different places, who spoke and wrote multiple languages fluently, to work with a figure like that needs a team of people who bring different perspectives to his work. This project is evidence of that character and that is unique to UO.

FM: When you research and teach a multilingual, transnational revolutionary figure, you are educating students about values, actions and modes of writing. The knowledge that this thinker existed, this is how they carried out their actions, this is how the work was perceived by his contemporaries, it provides an educational impact that is huge.

—By Jenny Brooks, College of Arts and Sciences