Experiential Learning | Research & Innovation | Community Impact | Career Preparation | Teaching Excellence | 21st Century Liberal Arts | Building Community | Good Vibes | CAS Spotlights | All Stories | Past Issues

Learning from Aliens

DECEMBER 2, 2024

Storytelling that mixes fantasy, reality and travel beyond Earth isn’t new. These types of stories typically ask “what if” questions to examine the consequences of human cultural behaviors.

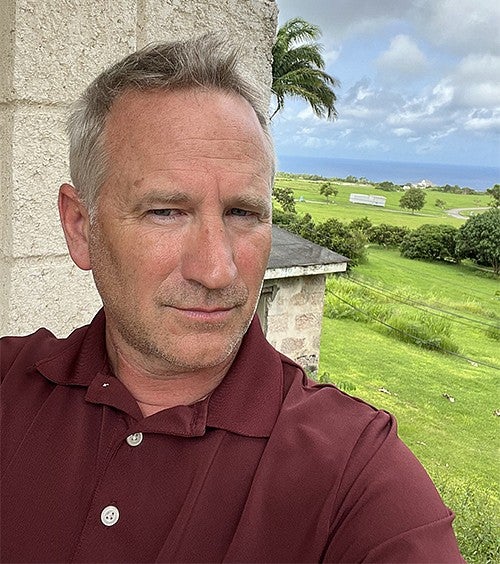

Phil Scher, a professor of anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences, does the same in his Anthropology and Aliens course, using speculative fiction and its subgenre, science fiction, to teach anthropology and challenge students' assumptions.

Science fiction often presents alien species, fictional societies or future human societies with vastly different cultural norms. According to Scher, this helps students grasp the concept of cultural relativism—understanding that norms and practices are not universal but shaped by specific contexts. By seeing "human" issues reflected in alien contexts, students can examine their own cultural assumptions.

“I've always been interested in science fiction and fantasy, even as a kid,” says Scher, who is also a professor of folklore and the department head for both Cinema Studies and Theatre Arts. “The creation of alien races by writers, for example, is a way to look at how those authors unconsciously channel things like colonialism and racism, even if they're trying to create empathetic or sympathetic alien races. It shows how deeply we hold ideas about other cultures and societies.”

Scher’s primary research as an anthropologist—someone who examines human societies and cultures and their development—focuses on the Caribbean and Caribbean diaspora, but he enjoys teaching topics outside of his research as well.

In Anthropology and Aliens, a 100-level course in the Department of Anthropology, students examine speculative and science fiction to learn how societal structures influence behavior and culture—similar to how anthropologists study real-world societies. Using science fiction as a teaching tool in anthropology courses provides students with imaginative spaces for rethinking core anthropological concepts, fostering critical thinking and challenging them to envision a plurality of human and non-human experiences.

Speculative fiction vs. science fiction

Science fiction and speculative fiction are similar and sometimes used interchangeably, but they do have a couple distinct features.

Speculative fiction looks at alternative outcomes of real events, asking the anxiety-based question, “What if?” Science fiction, on the other hand, tends to be focused on technology and how that technology changes or relates to the future.

Scher’s personal interest lies in a subgenre called anthropological science fiction, which focuses less on technology and more on the cultural and social dynamics of alien worlds. Ursula Le Guin’s Left Hand of Darkness, published in 1969, is an example of this subgenre. She intentionally created aliens that switch sex at different points in their lives and asked how that would change the way people think about gender and sexuality.

“Anthropological science fiction imagines concepts of a very different type of culture or society that would be alien to us,” Scher says. “The alien culture is used to throw into stark relief how we are in the world, or what our beliefs are, or what our assumptions are about being human or the cultural elements that we take for granted and then project a possible alternative, questioning the notion of what being a human is.”

Using sci-fi to challenge human agency

That’s why, in the development of Aliens and Anthropology, Scher used the original 1982 Blade Runner film as part of the curriculum. The “aliens” in the film aren’t from another planet but are human-like robots known as replicants who challenge the way viewers think about what being a human is.

Although the replicants have some brutal tendencies, the audience ends up feeling some empathy for them because they're trying to survive, and they have been created by a powerful corporate structure to be highly gifted yet extremely powerless. As the audience follows their journey, they come to realize that someone who was presented as human is a replicant.

“When we realize the robots don’t know they’re robots, it gives us pause to think about how much autonomy we have over our own lives,” Scher says. “To what degree do we control our own decision making and to what degree are we influenced by power structures and corporate societies?”

Through examining the film, students explore essential questions such as what it means to be human.

“We often think there are bright lines between humans and robots or animals, like our capacity for agency, empathy, morality, memory, consciousness and self-reflection,” Scher says. “But what if these qualities were simply the result of certain kinds of programming? That's part of anthropology, too. Issues that are brought up in the film provide amazing teachable content about how we know who we are.

Anthropology and Aliens, found in the course catalog as Anthropology 119 and currently taught by a rotation of different anthropology and folklore professors, highlights the impact of taking a broad range of core education courses. Students walk away with not only a greater appreciation for these stories, but also a sharper awareness of the world around them.

—By Jenny Brooks, College of Arts and Sciences