Experiential Learning | Research & Innovation | Community Impact | Career Preparation | Teaching Excellence | 21st Century Liberal Arts | Building Community | Good Vibes | CAS Spotlights | All Stories | Past Issues

January 8, 2024

CAS Earth Scientists Prepare for the Big One

At any moment, the “Big One” could hit the Pacific Northwest.

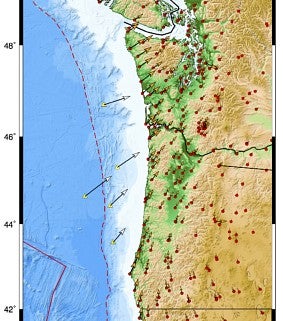

For more than two minutes, the 9.0+ magnitude earthquake will shake so violently that heavy furniture will catapult off walls, the ground could liquefy, and many buildings and critical infrastructure are at high risk of collapse. Once the shaking subsides, a tsunami—which could range from 10-30 feet tall—is expected to hit coastal communities.

Add in the possibility of a massive earthquake happening on a winter night—as the most recent one did when it shook on January 26, 1700—and it’s a terrifying scenario that will transform the region west of the Cascade Range, which runs from northern California through Oregon and Washington and ends in southern British Columbia, Canada.

Nothing can be done to stop the Big One, but, as seen in places like Japan, preparation can minimize its impacts. Earth scientists in the College of Arts and Sciences are working with public officials and offering grant money to scientists throughout the country to prepare for the inevitable moment.

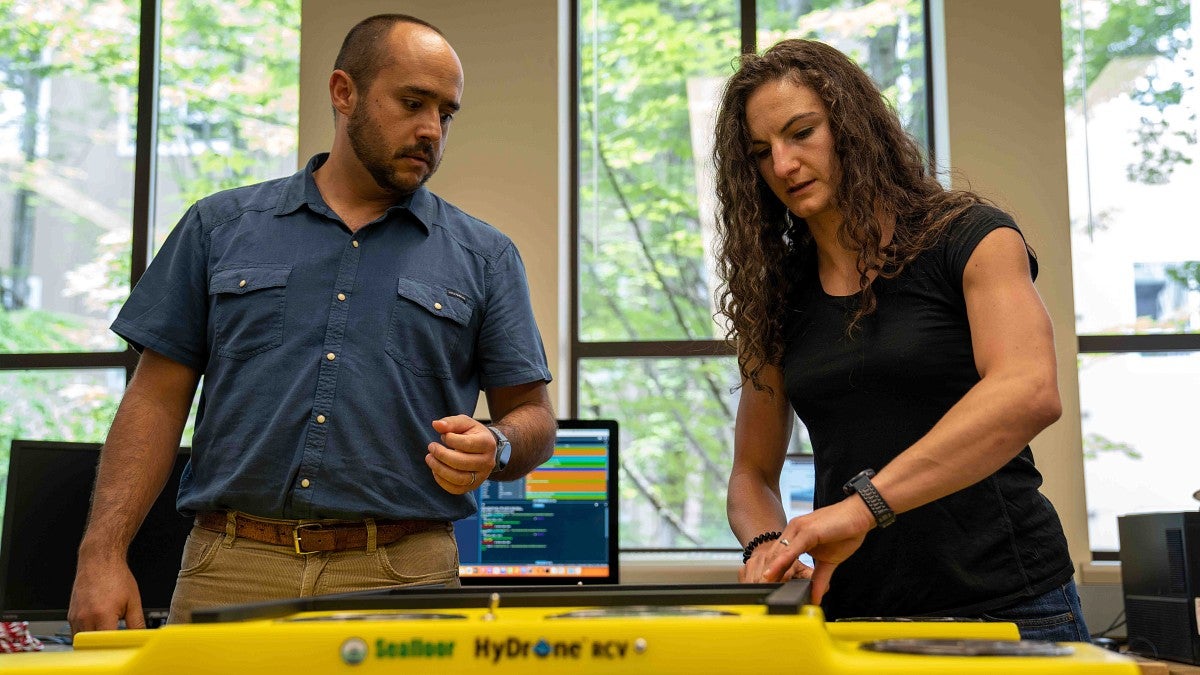

Funded by a five-year, $15 million National Science Foundation grant, the Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Center (CRESCENT) is the nation’s first subduction zone earthquake hazards center. The center is led by three Earth sciences faculty members in the College of Arts and Sciences: Diego Melgar, Valerie Sahakian and Amanda Thomas.

The center is focused on furthering its three goals: understanding the Cascadia subduction zone, diversifying the geosciences, and increasing collaboration between researchers and policymakers to communicate hazards related to the Big One.

“One of the key things coming out of the center are the fundamental science products that we need to move the science forward,” says Valerie Sahakian, an Earth sciences associate professor and a co-principal investigator at CRESCENT. “Agencies, groups and communities that are already doing science related to Cascadia can enhance their findings for what evacuation routes should look like, for example.”

Preparing for the inevitable

On a crisp October day at the University of Oregon, hundreds of people, including public officials and scientists, gathered to kick off the CRESCENT center. The meeting was the first of an annual gathering organized by CRESCENT to facilitate connections between Earth scientists and policymakers to better prepare for the Big One.

“There’s absolutely no way that we can accomplish the things we want to, even some small percent, without the center’s partnerships,” Sahakian says. “I’m pretty excited about what this means for opportunities going forward.”

CRESCENT encompasses researchers from 16 institutions around the US. Led by Melgar and co-principal investigators Amanda Thomas and Valerie Sahakian, both of whom are associate professors in the Department of Earth Sciences, the center also includes co-investigators from Oregon State University, Central Washington University and the University of Washington.

CRESCENT plans to share its NSF money through grants to help advance research on the Cascadia subduction zone, starting with a small grants program. Researchers can apply for up to $30,000 to conduct research that relates to the Cascadia earthquake and aligns with at least one of the center’s three goals.

“The center will conduct research that is directly relevant to earthquake and tsunami hazards but too ambitious for any one scientist to take on individually,” says Thomas, the chief technical officer for CRESCENT. “Our goal is to create community-endorsed research products that are immediately relevant for science and hazard estimates.”

A looming threat

As the Pacific Northwest developed over the 20th century, most scientists ignored accounts from Japanese and Native American histories that warned a massive earthquake was possible.

Unlike California, where earthquakes razed cities in the early 1900s and changed infrastructure standards, the Pacific Northwest didn’t adopt regulation changes until more than 30 years ago.

“The big earthquake might not happen in our lifetimes, but if it were tomorrow, nobody would be surprised,” says Melgar, who’s also the Ann and Lew Williams Chair in Earth Sciences. “And if it were tomorrow, the consequences would be pretty scary.”

CRESCENT center will work with officials and scientists to investigate the hazards that could happen after a 9.0 earthquake, with the aim of improving resilience and preparedness. Besides the shaking effects of the initial earthquake, which could destroy bridges, freeways and even dams throughout the region, the Big One is expected to cause a tsunami—but how high and where it will hit is still has significant uncertainties.

Melgar hopes the research CRESCENT will support communities with infrastructure planning. An engineer designing a bridge, building or power plant, for example, needs to know what types of materials to use to withstand an earthquake’s shaking.

“Our goal is to have research and build a workforce that is trained and willing to take on these problems so that when the earthquake happens, it doesn't look as apocalyptic as it will look if it happens today,” Melgar says. “It's going to take time. But if we don't start now, then when?”

Diversifying the earth sciences

While the CRESCENT team explores the potential impact of the Cascadia fault, they’ll also address one of Earth science’s biggest faults: a lack of diversity.

According to a 2018 article in the research journal Nature, geosciences were the least diverse of all STEM fields. The data showed that most PhD degrees (86 percent) went to white people while the number of underrepresented minorities — including Native American, Black and Hispanic—has been stagnant over the past 40 years.

“One of two things are possible,” Melgar says. “Either minorities are just not good at the geosciences—we call that racism—or there are structural barriers that we need to work to remove so that everybody can participate.”

To help remove those barriers, the center plans to provide scholarships to bring in cohorts of students for mentorships. Barriers to earth sciences aren’t only in the classroom and lab, Melgar says. Mentorship will help students navigate barriers to the professional world, such as creating CVs, finding jobs in the field, writing cover letters and more.

Diversifying the Earth sciences is a way to bring more voices to the discipline who can research science questions related to communities of color, says Sahakian.

“One example might be whether or not we're listening to the oral histories of Indigenous people who have been here and their knowledge about earthquakes and shaking in the past,” she adds.

But most importantly, increasing diversity in geosciences is a moral obligation, Melgar says.

"Right now, for whatever reason, people from minoritized backgrounds, they get to the geosciences and they do not feel welcome,” Melgar says. “You need to change the entire culture over a discipline so that diversity is something we don't even have to think about anymore. We're far away from that, and it starts with representation.”

—Henry Houston, MA ’17 (international studies) is a communications coordinator for the College of Arts and Sciences.

Bringing Scientists and Communities Together

The CRESCENT center has 16 participating institutions:

- University of Oregon

- Central Washington University

- Oregon State University

- University of Washington

- Cal Poly Humboldt

- Cedar Lake Research Group

- EarthScope Consortium

- Portland State University

- Purdue University

- Smith College

- Stanford University

- University of California, San Diego - Scripps Institution of Oceanography

- University of North Carolina-Wilmington

- Virginia Tech

- Washington State University

- Western Washington University