Experiential Learning | Research & Innovation | Community Impact | Career Preparation | Teaching Excellence | 21st Century Liberal Arts | Building Community | Good Vibes | CAS Spotlights | All Stories | Past Issues

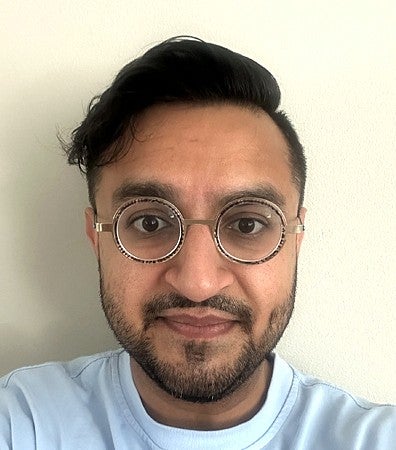

Meet Ali Malik

MARCH 5, 2025

What is your research focus?

I'm looking right now at the introduction of what's called “digital agriculture” in the Global South. Broadly, that’s the use of Big Data and AI and machine learning technologies and food systems, and that's been happening in North America for a little over 10 years. But it's just kind of en masse, being rolled out in different parts of the Global South, really, within the past five to seven years.

Part of that drives my curiosity is if these technologies are actually going to do what they promise. We're being told by dominant agrifood institutions, industry, and private actors that we just need to get more granular information about farming, and we just need better tech, and we need to teach farmers how to be modern tech people, and therefore that'll fix everything. This is a story we've heard within the Western development establishment for quite some time: “We need to teach them how to be like us. We can teach them sort of different things and use technology to sort of facilitate that.” And I’m trying to make sense of what actually happens when that all collides, and what that might able to tell us about the contemporary but changing relations between capitalism, imperialism, and technology.

What various scholars have shown us is that technology is always reshaped by human agency in ways that we had never really imagined. And it's not always for the better, but it does mean that these things are not sort of linearly put on the ground and then they just play out exactly the way that the planners thought they would. They're always disrupted. They always create new things. They can open up new avenues for sometimes political contestation for marginalized communities.

That's part of what I've tried to show in my research thus far: every time the Indian state tries to sort of get a hold, to control its small holder farmers, through technology, the farmers somehow find a way to use that as a way to sort of organize or it provokes political contestation when the state thought they would sort of tamp that down.

Why do you prioritize interdisciplinary teaching methods?

In much of my early education, things were largely discrete and bounded, and disciplines contributed to that. If you're trained as a lawyer or an economist, for example, you're going to tend to see a problem through the specific sort of lenses that your discipline has trained you to see. It makes sense and there's definitely value in that, but what I've learned thinking about big, both ongoing and historical global crises, is that they're always bound up with other things that we may have not fully considered.

That is part of what I try to teach and develop with my students. I want them to have a “toolbox” of ideas, frameworks, concepts, theories, and research methods as well, of how to answer the questions that you're curious about in relation to these big problems, and what that means for your place in the world.

I don't think any major global problem is discrete and doesn't have connections across space or time to other people, places, you know, histories as well. I think my task, and one of my objectives, with UO students is to develop the toolbox to make these connections in order to produce change.

Why University of Oregon?

There is a serious commitment to the humanities, to the social sciences, to critical thought, and to critical research here. It became really clear to me that the institution and the school have the commitment to inter- and transdisciplinary sort of work.

—Grace Connolly, College of Arts and Sciences