Experiential Learning | Research & Innovation | Community Impact | Career Preparation | Teaching Excellence | 21st Century Liberal Arts | Building Community | Good Vibes | CAS Spotlights | All Stories | Past Issues

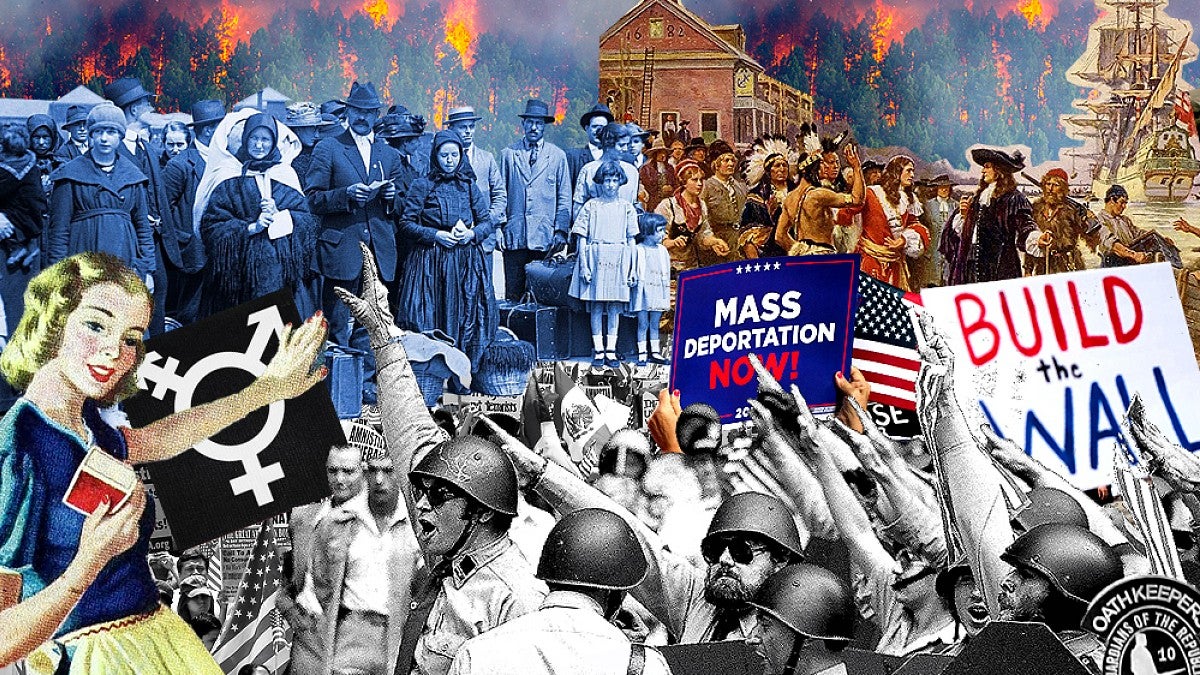

Environmentalism or Ecofascism?

BY JENNY BROOKS

APRIL 7, 2025

When someone says they’re fighting climate change, it sounds like a noble cause. But some people understand the increasingly warming planet as a call to engage in violence and oppression against “undesirables” by way of ecofascist policies.

As the effects of climate change become more apparent, Assistant Professor and Mokin Fellow of Holocaust Studies Miriam Chorley-Schulz is helping students parse how ecofascist ideology is resurging globally in response.

In her course on ecofascism (GER 407/507), Chorley-Schulz explores the origins of ecofascism as a political ideology that has historically tied extreme ethnonationalism to ideas about nature and its preservation—and how these same ideas are reactivated globally in extremist right-wing politics today.

The course curriculum starts with a deep dive into how “Nature” is used to construct nationhood, race, gender and sexuality. Students learn how political movements such as National Socialism (Nazi party), Italian fascism and the Ku Klux Klan used nature to justify their eliminatory principles and acts.

“I would say that anyone who has a vested stake in being alive on this planet—which is everyone—would have a great deal to gain from delving further into the topic of ecofascism,” says Henry Els, a master’s student in German and Scandanavian studies who took Chorley-Schulz's course.

What is ecofascism?

Ecofascism is not climate change denial, Chorley-Schulz says. Rather, it is a racist and xenophobic ideology with its own environmental agendas.

Ecofascists believe only some people should have access to resources like land, food and energy and that other people, usually underprivileged and vulnerable populations, are disposable and should be cut off from those resources by way of ever more restrictive migration regimes and other forms of eliminatory violence.

When followed to its logical conclusion, “it’s environmentalism through genocide,” author and activist Naomi Klein succinctly summarizes.

Manifestos left by the Christchurch, New Zealand, and El Paso, Texas, white supremacist terrorist shooters and self-identified ecofascists are proving her point. They build, however, on a much longer history of right extremist ideologies that attach themselves to ecological questions and agendas.

Ecofascist ideas are rooted in the rise of capitalism, gradual colonization, primitive accumulation and resource extraction around the world.

One example of ecofascism students learn about is western expansion in the Americas and the removal of Indigenous people from their lands, including the subsequent genocides, to make room for white settlers. Another example is the Nazi party’s project to both create their own superior “Aryan race” with an “organic” relationship to “Nature” and to simultaneously eliminate those they considered “non-Aryan” as they expanded territorially and colonized German Lebensraum (living space) across occupied Europe.

Colonial expansion across the globe followed similar patterns, with Indigenous populations displaced or murdered in the name of territorial expansion and resource control. The long-term consequences of these processes are still felt today, as many formerly colonized nations are still recovering or suffering from the ongoing devastation, such as on the African continent, in Southeast Asia and in the Americas.

These historical examples resonate in the class because the core ideas reverberate today. Supporters of ecofascism tend to act in defense of the “natural order” of things—a conservative view that naturalizes the gender binary; hierarchizes people and allocates specific, unchangeable roles to them; and erects physical and metaphorical borders between them to “restore the balance of nature.”

“One of my biggest impressions from this class was its relevance. It is incredibly relevant to recent political trends,” Els says. “It seems to lie at the heart of many far–right political movements, especially today—though not without historical precedent by any means.”

Today’s ecofascist projects

The trad wife phenomenon can be seen as a current expression of right-wing movements' ecofascist visions. In addition to believing that gender and sexuality are unchangeable and have prescribed roles, certain trad (traditional) wives and their husbands are propagating an anti-urbanist, “back to nature” agenda.

Implicitly or explicitly white supremacist, they understand their sole mission as reproducing the white population to avert the “big replacement.”

“It's an attempt to go back to an imagined past that was allegedly better, which is always part of fascist desires,” Chorley-Schulz says.

But it doesn’t solve the climate crisis; it makes it worse.

“The contradiction that you see with climate change is you cannot go back in time. Their environmental policies are accelerating climate change even as fascist leaders allegedly want to go back to that imagined past,” Chorley-Schulz says.

The anti-migration movement, both globally and in the US, is another example of a right-wing ecofascist ideology.

“It is true that millions of people are on the move because of climate change. This is what ecofascists also understand,” Chorley-Schulz says. “Their solution, however, is not to stop climate change, but to stop the movement.”

It’s important to note that ecofascist policies don’t just target migrants. Members of the LGBTIQA+ community, people with disabilities, people who practice a religion other than Christianity, and people of color are all examples of groups impacted by ecofascist policies. They were also all groups targeted by Hitler and the Nazi party.

Checking positions for ecofascist intentions

Ecofascism is a complex ideology that requires careful explanation. As Chorley-Schulz says, you can’t just list what is and isn’t ecofascism, especially when it’s coded with concern for nature.

Instead, you have to give people the tools to ask questions and then deconstruct the ideas, policies and movements.

Classes like Chorley-Schulz's ecofascism course empower students with information they can use to ask critical questions and engage in discussions to better understand complex topics.

“The seminar experience sharpened my critical perspective for analyzing this type of discourse,” says Teppei Fukuda, a doctoral student of Japanese literature in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures. “I work on Japanese aesthetics associated with the four seasons. It was such an exciting experience to study a similar topic in a very different cultural context and to learn that similar ideas about climate went in different directions in the two countries.”

Building community and standing in solidarity with the most underrepresented members of society is another way of fighting ecofascist ideologies. The classroom is one place to both gain the tools and build community.

"This class, and Miriam, really challenged me to look at views I had been raised with, taught and fed by the media over my lifetime,” says Jenene Carver, a double major in political science and psychology who plans to graduate in 2027. “I have shared both the material as well as discussion topics far and wide within my personal community to help them look at their own internal biases and environmental views.”

Climate change is only growing in relevance. Understanding ecofascism—in the classroom and beyond—is essential to preventing it from taking hold and causing catastrophic damage the way it has in the past.