Experiential Learning | Research & Innovation | Community Impact | Career Preparation | Teaching Excellence | 21st Century Liberal Arts | Building Community | Good Vibes | CAS Spotlights | All Stories | Past Issues

A Brain on Music

FEBRUARY 3, 2024

Daniel Levitin didn’t always plan on studying the brain. In fact, he initially left college to pursue a music career.

Now with six consecutive New York Times bestsellers, over 100 published scientific articles, 17 gold and platinum album awards and a pilot's license under his belt, the renowned neuroscientist and University of Oregon alum recently returned to his alma mater to find the campus has changed . . . almost as much as he has.

“They renovated all the drywall and the lights and the ceilings, but these look like the original windows,” the avid do-it-yourselfer says after visiting Straub Hall’s updated classrooms and lab spaces, which were modernized during the 1920s-era building’s overhaul in 2014. “The stairways were a little creepy back then, just falling apart. Now they're even welcoming! I could sit here on the landing and have a coffee and look at the birds out the window.”

Since earning his PhD from the Department of Psychology in 1996 under the joint supervision of professors emeriti Douglas Hintzman and Michael Posner, Levitin has become one of the most prominent figures in cognitive science. Much of his work examines the connection between music and the brain, such as how music can serve as a mechanism for memory retrieval. For instance, recalling a particular song can transport you back to a specific place or time in your life.

“The kind of knowledge that I had acquired in music theory and music practice before coming to UO was something that not every cognitive psychologist had," Levitin says. “So Mike Posner advised me to combine the two. That was really great advice."

Levitin’s research has significant implications for therapies related to cognitive diseases, including those affecting Alzheimer’s patients. But his work stretches far beyond the scientific community.

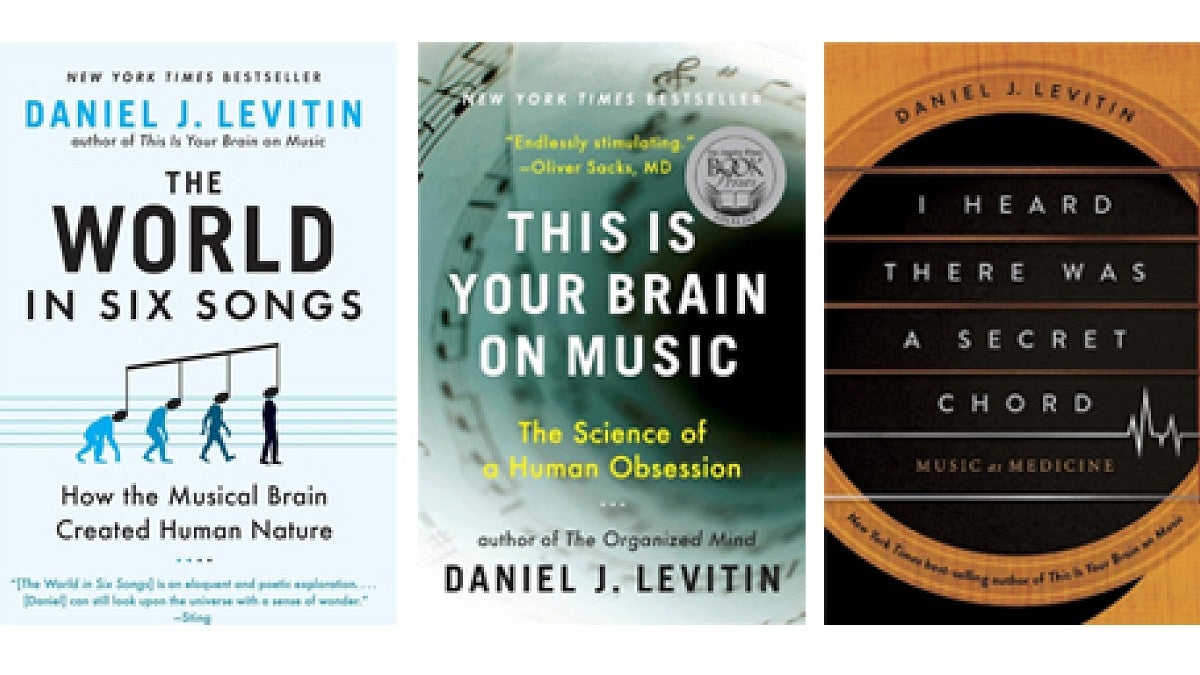

His bestselling books, including This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession and The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature, explore the intersection of music theory, psychology, evolution and culture to explain why humans have such a deep connection to music. His 2014 book The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload was a business bestseller, and Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella bought a copy for every manager. Levitin's newest book, I Heard There Was a Secret Chord: Music as Medicine, was named one of Smithsonian's 10 Best Science Books of 2024.

During a recent visit to campus to donate his papers to the UO Libraries’ Special Collections and University Archives, Levitin delivered a guest lecture about his new book to students in a course on cognitive psychology taught by Nicole Dudukovic, director of the UO’s Neuroscience Program.

“He is able to speak and write about these topics in an accessible and engaging way,” Dudukovic says. “Dr. Levitin’s writing gets people excited about brain science.”

The power of music

Before embarking on his scientific journey, Levitin enjoyed a successful music career.

He played guitar, bass, saxophone and sang with noteworthy musicians, including Mel Tormé, Rosanne Cash, Victor Wooten and Neil Young. He also found success as a sound engineer and producer for the Grateful Dead and Stevie Wonder.

Levitin’s passion for music has its roots in childhood. Growing up listening to "very brittle-sounding 78 rpm records,” his mind was constantly filled with the sounds of music—from big band jazz to classical.

“What I understand now as a neuroscientist is that during those early years, roughly between ages 0 and 6, my brain was literally wiring itself to those sounds, rhythms and chord progressions,” he says.

At 8 years old, Levitin began taking private clarinet lessons.

“I remember blowing in the instrument, and it sounded terrible,” he says. “I remember my fingers didn't quite cover the holes, and I had to press down harder. But I also remember the thrill of being able to make this decidedly awful sound come out of an instrument, knowing that if I kept with it, it might someday sound good.”

In a short time, he was consumed by music, playing multiple instruments and joining the orchestra, the jazz band and the marching band. He even learned how to conduct. “I found myself pulled towards music, impelled towards it. I found great joy in it,” he says.

Levitin's early musical explorations planted the seeds for an electric, eclectic career, encouraging him to explore a variety of professions, from playing saxophone in a band to producing music for established artists to studying cognitive psychology, and then writing popular press articles for magazines (The New Yorker, The Atlantic). He is also a regular book reviewer for The Wall Street Journal; one of his recent reviews was of UO Professor Garrett Hongo's poetry book, The Perfect Sound.

“It gave me a sense of possibility that you don't have to stick with one thing,” he says. “That's really been my career, not sticking with one thing.”

The intersection of music and the mind

When the music industry began to implode in the 1990s, after its failure to adapt to the digital revolution, Levitin decided it was time to return to school.

“I was, at that point, 33 years old and without a bachelor's degree,” he says. “A bunch of us in the music business decided we should all have a backup plan in case the music business didn't work out.”

Before dropping out of school, he had been studying for a bachelor's degree in mathematics at MIT. But several of his former professors told him he was now too old to become a successful mathematician.

“They said, ‘Mathematicians make their discoveries in their 20s. You could probably do math and get a job as a mathematician, but it’s going to be harder for you,’” Levitin says.

However, Roger Shepard, a mathematical psychologist at Stanford, suggested he could study mathematical models of cognitive processes and still effectively be a mathematician. After earning his bachelor's degree in cognitive psychology from Stanford, Levitin arrived at the UO to pursue his master's and PhD.

—Daniel Levitin, neuroscientist

At that time, UO researchers were investigating a broad array of topics, including psycholinguistics, motion and visual perception, neuroimaging and memory.

In his third year as a graduate student, Levitin received career-altering advice from faculty advisors Douglas Hintzman and Mike Posner, both of whom are well-established in the field of cognitive psychology.

“They said, ‘There are a lot of people studying memory, psycholinguistics and decision-making, and it's a competitive job market. You've got this background as a musician. Why don't you combine the two?’” Levitin says.

That expertise in music theory and practice was rare among academic psychologists.

“Mike, in particular, claimed to have a tin ear and be tone deaf,” Levitin says. “Mike says he only knows two songs; one of them is ‘Yankee Doodle,’ and the other one is not. But that didn't stop him from giving me great advice about how to look at music cognition in the broadest terms, as a window into the brain, mind, attentional processes, categorization and memory.”

Although this niche appears to be an untapped scientific field, Levitin notes that he’s not a pioneer in considering the relationship between music and cognition.

“This goes back to the Greeks,” he says. “Pythagoras had theories about why music is pleasing and why certain melodies and intervals have appeal. Aristoxenus argued that it’s not about frequencies, it's about the brain. There's something going on in the brain that makes them pleasing. So that idea is 2000 years old.”

Thanks to advancements in technology and his expertise in effectively communicating his work to broad audiences, Levitin has expanded the field of neuroscience by researching music’s impact on cognitive processes and furthering our understanding of the human mind through the lens of music.

But Levitin hasn’t stopped there. He has continued to pursue all sorts of avenues, from stand-up comedy to working as a script consultant for the popular TV series The Big Bang Theory. His eclectic career path embodies the idea that “you don't have to stick to one thing.”

“When I see something, I want to try it,” he says. “I want to know what it's like to do it.”

—By Leo Brown, College of Arts and Sciences