Experiential Learning | Research & Innovation | Community Impact | Career Preparation | Teaching Excellence | 21st Century Liberal Arts | Building Community | Good Vibes | CAS Spotlights | All Stories | Past Issues

Ernesto Javier Martínez, associate professor and head of the Department of Indigenous, Race, and Ethnic Studies, has launched a crowdfunding campaign to turn his short film 'La Serenata' into a full-length movie.

Turning Pain into Power: Meet Ernesto Javier Martínez

Ernesto Javier Martínez grew up in a time and place that rarely showed positive representations of what queer kids could become. So the head of the College of Arts and Science’s Department of Indigenous, Race and Ethnic Studies became a little bit of everything: professor, activist, author, filmmaker and, arguably, a healer of sorts.

Equipped with an academic mind, a poetic heart and the will to effect change, the associate professor of ethnic studies has turned his professional career into a personal healing journey—not only for himself, but for the students and communities he serves.

Inspired by his work with queer Latinx communities, Martínez became a children’s author in 2018 with his award-winning book When We Love Someone We Sing To Them, illustrated by Maya Christina González. That led to his 2019 short film La Serenata, directed by Adelina Anthony, which won multiple awards—including the prestigious Imagen Award—and was licensed by HBO Max.

Bolstered by his unexpected success, Martínez recently wrapped up a crowdfunding campaign to turn his short film into a full-length movie. The screenplay already has won multiple awards and garnered funding from departments and centers across the University of Oregon.

What makes Martínez’s work so resonant is the way it weaves queer themes with themes of culture, music and human connectedness, says Monica Carter, national director of Lambda Literary’s LGBTQ Writers in Schools program, which connects K-12 students with LGBTQ+ authors.

“When I saw Ernesto do a visit with students, I was so impressed with the way he engaged with the young kids. He really understood how to talk to them,” she says. “When kids see themselves represented in a book, that impact at such an early age means lot.”

That’s why Martínez is determined not to let the accolades distract him from what’s important: the work.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Oakland, California, in a part of town that is predominantly Black and Latino. It was a working-class neighborhood that has a lot of activist history. It’s also a place that required a kind of toughness that often was hard for me as a soft queer kid.

I have fond memories of Oakland. It was so formative, but also there was a lot of bullying. When you live in a violent place it really is, like, daily negotiation. You just really do wonder, ‘Is today another day where something bad will happen?’ It really stays with you.

What was your childhood like?

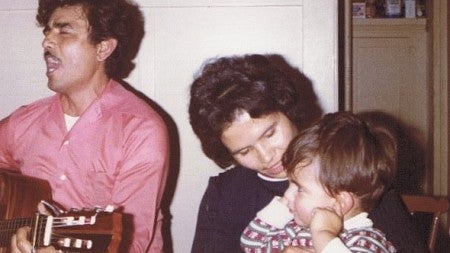

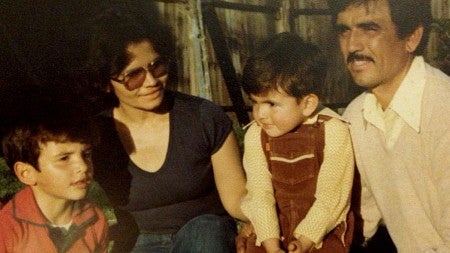

Our family is super tight knit. My father was Mexican and immigrated to this country. My mom migrated from Puerto Rico when she was 12. We would move back and forth between Mexico and the United States.

As tough as Oakland was, Mexico was tough on me in another way because there was a certain kind of gendered play that made it very strict. As a kid in the US, I could play with girls, but in Mexico it felt more marked.

How did those experiences shape you into who you are today?

I identify as Chicano. But although I was born here and went to most of my schooling here, in some ways I feel like an immigrant. Our friendship circles were other immigrants.

In ethnic studies, scholars often talk about being in-between. While that often doesn’t feel good, not knowing where you belong, a lot of us have theorized that “in-betweenness” as a really rich place, a place of possibility.

What was your college experience like?

I studied English at Stanford in the 1990s and I loved it. I had the opportunity to study with a ton of people of color and queer people. I took an enormous amount of classes dealing with race, gender, and sexuality. It was just beautiful, and I felt really loved there.

When I went to Stanford, I immediately came out. Back then, coming out was more of a big deal than it is now because there was so much anxiety around it. It was the ’90s, during the AIDS crisis, and there was a lot of stigma around being queer.

How did your parents react to your coming out as queer?

My parents, overall, were super-supportive. My mom was 100 percent a lioness. She’s a quiet person but she’s like a lioness in terms of LGBT issues. Her instinct was to protect me.

My dad had a longer turnaround time. That night, when I told him, we cried. He said it hurt more than his mom dying. But he was really just processing, I think.

The next morning, he drove me back to Stanford. We were both silent, and this man, he reached over for my hand and held my hand the whole ride. I couldn’t speak, the emotions were in my throat. I was looking out of the window. He had said so many hurtful things—it’s not that I forgot all those things, it’s that holding a hand, for a kid who’s never been able to hold hands with someone in public, it was a real gesture of care from someone who was a man’s man. So I thought, ‘Look at him trying.’ It was lovely. My dad had my back.

What inspired your academic work as a professor?

I’ve always been interested in the violence that happens to people at the level of knowledge acquisition or when they’re giving testimony to what they know. We call it epistemic violence.

There’s this violence that happens to you when your society robs you of information and you can’t make sense of the world or interpret your life accurately. When someone spits into your face in elementary school and calls you a fag and then other people laugh and your teacher doesn’t protect you, and all you’re left with is the shame of that, society robs you of information about who queer people are to their communities.

And then there’s testimonial violence, which is violence that happens to you when you’re trying to give testimony to what you know and people say, ‘You’re too loud. I don’t give you the floor. What are you talking about?’ So, they question your testimony.

Your book and film both have a lot of heart. Where does that come from?

I think it comes from touching down on pain.

Queer adults have not often had pleasant childhoods in homophobic societies. Writing stories that center queer youth presents an opportunity to look back on our own lives and heal. Creators like myself hover over past experiences, often touching down on much hurt, and now from those very real experiences we share with queer youth what we’ve learned about the world.

We write because we want to heal our inner child, yes. But we also want to morph that and not carry the pain but transform it into a lesson for kids.

Did you have any inkling when you wrote your film that it would achieve such success?

Not at all. I imagined it as an activist project. We would make the film and take it to the community and host workshops around it with families. Then, on the film festival circuit, I saw that people were picking it up and it started getting awards. It took on a life of its own.

I wanted to put the film in community film festivals—not just the mainstream ones, but Latinx film festivals that don’t get a lot of play. My goal was to go where Latinos would see the film. There was one festival I thought was small, but it turned out they had this secret HBO Latinx short film competition. It was happenstance, but also maybe a little connected to the healing of it all.

Your work has been described as the type of work that’s needed to help transform society. What sort of society do you envision?

I work with a lot of organizations that have big vision statements that imagine a world free of violence. I love those big visions, but it feels odd right now to say I imagine a world that is violence-free.

What I envision is people being honest with themselves, using literature and films like ours as opportunities to explore and challenge their most basic presuppositions about queerness as a valuable and desired feature of our shared world. I want a world where someone can say, ‘I want to be better, but I realize I have never been taught how to love you in ways that make you feel free.’

Of course, I want a violence-free world, but barring that, I want a space where everyday people, through incremental acts of courage, can lean away from their own prejudices and open their minds and hearts to queer youth.

—Nicole Krueger, BA ’99 (journalism), is a communications coordinator for the College of Arts and Sciences.